RESEARCH AT WESSELMAN WOODS

As a State Nature Preserve and National Landmark, we want to ensure that Wesselman Woods and Howell Wetlands are conserved and protected for posterity. It is exigent that we continuously learn and understand the ecological, environmental, and social aspect of Wesselman Woods and Howell Wetlands.

RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

As a State Nature Preserve and National Landmark, we want to ensure that Wesselman Woods and Howell Wetlands are conserved and protected for posterity. It is exigent that we continuously learn and understand the ecological, environmental, and social aspect of Wesselman Woods and Howell Wetlands.

We encourage and invite researchers to study and teach us, Evansville, and the academic community about our urban ecosystems.

If you are interested in pursuing research at Wesselman Woods, Howell Wetlands, or our Nature Playscape, contact Cindy Cifuentes, Director of Natural Resources and Research at Wesselman Woods.

Former Director of Natural Resources, Cindy Cifuentes, installs a camera trap

Wesselman Woods Wildlife Watch

Want to know if there’s a red fox trotting around Wesselman Woods? Curious to know what happens in the woods when no one is looking? We’ve got you covered.

Wesselman Woods Wildlife Watch is a new camera trap project on the preserve composed of nine trail cameras on various transects. These cameras are deployed for 30-days a total of four times a year during the months of January, April, July, and October. After each deployment period, thousands of photos are gathered from these cameras and uploaded onto our citizen science page on Zooniverse. We’ve caught all sorts of things on camera from box turtles and snapping turtles all way to barred owls and coyotes!

Why is this important?

Understanding urban wildlife behavior is more important now than ever before. As the human population continues to rise exponentially and wildlife is forced into closer proximity to humans, we will begin to see increased human-wildlife conflicts. By creating this camera trap study, we are able to understand what wildlife is living in the city and how it utilizes an urban forest.

There are various large-scale camera trap studies around the U.S. that are trying to better understand urban ecology through the Urban Wildlife Information Network. Although Evansville is not as big as these cities, Wesselman Woods has unique landscape characteristics. The differences between greenspaces in cities and the wildlife they house is critical to understanding urban ecology, habitat connectivity, and invasive species management. Biologists have a basic understanding as to why there are so many differences in wildlife occupancy between cities. By contributing to this research question we are not only contributing to urban ecology theory but we are also enforcing the importance of greenspaces and biodiversity in cities for better city planning and conservation.

The overall goal of this project is to collect meaningful data that will influence academia, foster community-wildlife relationships, and local policy.

How can you help?

All the pictures captured from each of our cameras is uploaded onto our citizen science page on Zooniverse. Here, you will be able to help us ID thousands of photos and contribute to meaningful data. Plus, you’ll have exclusive access to some of the cool wildlife photos we gather!

Just click on the hyperlink to our project page and a tutorial will guide you through the process. You’ll also be able to chat with other researchers and citizen scientists about the project as well. Happy tagging!

A small-mouthed salamander found at Wesselman Woods | Photo by Isaac Morris

Salamander SURVEYS

Wesselman Woods and Wesselman Park create a unique forest habitat for wildlife big and small… including salamanders! Salamanders spend most of their lives hiding under leaves, rocks, or logs in a state of torpor or hibernation. However, each spring, these amazing amphibians migrate en masse to begin their travels to mating pools. Luckily, Wesselman Woods and Wesselman Park are home to two large vernal pools where hundreds of salamanders gather.

With all this salamander activity happening in our neck of the woods, we absolutely take advantage of this research opportunity. Staff and volunteers walk around on rainy nights looking for salamanders and recording various data including:

species

length

location

temperature

direction

photos

Spring 2023 Count: 229

50 Northern Slimy salamanders

39 Spotted salamanders

5 Marbled salamanders

135 Smallmouth salamanders

Why are the 2023 and 2022 numbers so low? Could be a variety of reasons, including (but not limited to) colder nights, less warm rains, more extreme weather (storms), and having less volunteers for surveys.

For 2023, we were only able to survey four times (versus our typical seven surveys) due to these four reasons.

Spring 2022 Count: Total 349

44 Northern Slimy salamanders

16 Spotted salamanders

6 Marbled salamanders

283 Smallmouth salamanders

Spring 2021 Count: We recorded the following 476 individuals, our largest salamander population in Wesselman Woods history!

42 Northern Slimy salamanders

24 Spotted salamanders

2 Marbled salamanders

408 Smallmouth salamanders

Why are salamanders so important?

Salamanders, like many amphibians, are ecosystem indicators. This means that their presence indicates a healthy ecosystem. Because salamanders have permeable skin, they are very sensitive to drought and toxins in their environment. We are so lucky to have such a large population at Wesselman Woods!

Conservation Efforts

During the first warm rains of the year, salamanders will travel to the vernal pool in the middle of Wesselman Park. In order to get to this pool, salamanders will have to cross at least one road. Because we have collected so much data on location and direction of travel, it is safe to say hundreds of salamanders use the roads to get to and from the vernal pools. To ensure a safe salamander crossing-zone and lower mortality rates, we close off the roads around Wesselman Park every spring.

Sugar Maple TAPPING

Science can be tasty too!

January 2021 marked our 44th Annual Maple Sugarbush Festival. What’s maple sugarbush? It’s that special time of year when we tap our sugar maple trees at Wesselman Woods and collect as much sap as we can from our mighty sugar maples. We tap 16 of our sugar maples; we have many more sugar maples in the Nature Preserve but we only tap a select few. All the sap we collect is then poured into an evaporator and boiled into delicious maple syrup.

Sap Science

Sugar maples can only be tapped in the winter when temperatures are below freezing at night and above freezing temperatures during the day. This fluctuation in temperature is what causes sap flow in sugar maples. Negative pressure from freezing temperatures in the roots turns into positive pressure during the day causing carbon dioxide to expand in the tree, which causes sap release through the tapping holes. Tree sap is mostly made up of water, minerals, nutrients, and roughly 2% sucrose (sugar). This means we have to spend A LOT of time boiling down sap to get to that thick maple syrup.

Research

There is so much we have yet to discover about the science of sugar maple tapping. What determines the amount of sucrose content in sap? How does rainfall and temperature determine the amount of sap produced from one tree? Staff and volunteers take turns collecting sap every morning and afternoon and record temperature, rainfall, time, sap amounts, and sap condition to try and gather enough data to answer some of these questions. Our goal is to eventually gather enough data to see how climate change affects sap collection in sugar maples!

DEER STUDY

Effects of Deer Browse on Tree Regeneration

If you have ever walked the trails of Wesselman Woods, you have probably noticed lots of tree cages and flags within the forest. It isn’t for decoration, it’s for science! Thanks to Dr. Cris Hochwender and his students at the University of Evansville, we have a long-term tree regeneration monitoring study.

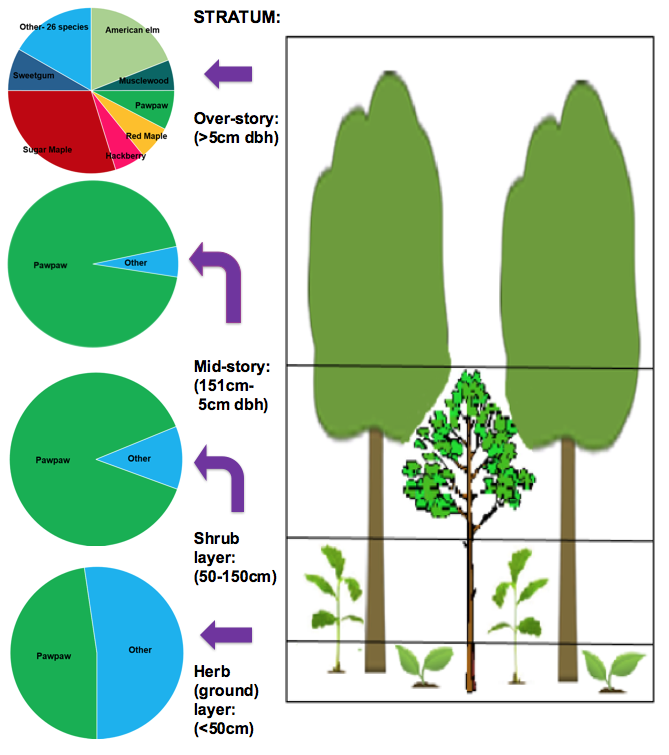

Deer threaten biodiversity by selectively browsing tree saplings. When deer selectively browse, they can alter the forest community by changing the relative abundance of tree species. Wesselman Woods Nature Preserve (WWNP) is an ancient forest of high quality. However, WWNP is small enough that deer can completely penetrate it and browse seedlings and saplings throughout the forest. Indeed, deer appear to have prevented most trees other than pawpaws from growing above one meter tall for the last 50 years. These pawpaws, coupled with the deer, may act as a barrier to regeneration for tree species important in the forest canopy.

To examine the challenge caused by deer and pawpaw, 60 plots have been established. In 30 of these plots, all pawpaw trees have been removed. In addition, across all 60 plots, saplings of overstory species have been caged (and paired with an uncaged individual of the same species); species in the study include oaks, hickories, maples, and other important species in the forest canopy.

This experiment will evaluate the effect of having a dense pawpaw layer and the effect of deer browsing. In addition, the experiment will examine the importance of the combination of pawpaw and deer browsing on the ability of saplings of canopy tree species to reestablish from saplings. The findings of this study will have application for forest management of WWNP, as well as management of forests in the Midwest.

For more information on methodology and results, read the 2016 publication.

THANK YOU

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the organizations and individuals who make our research and conservation efforts a possibility.

Lochmueller Group

Evansville Audubon Society

Eagle Scouts

Sherwin Williams

Sunbelt Rentals

University of Evansville

University of Southern Indiana